Belgrade

| City of Belgrade Град Београд Grad Beograd |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

| District | City of Belgrade | ||

| Municipalities | 17 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Dragan Đilas (DS) | ||

| - Deputy Mayor | Milan Krkobabić (PUPS) | ||

| - Ruling parties | DS/G17+/SPS-PUPS/LDP | ||

| - City council |

List

Goran Aleksić

Darko Božić Oliver Glišić Aleksandra Gojković Zoran Kostić Goran Kreclović Dejan Mali Darijan Mihajlović Željko Ožegović Nikola Pavić Mileta Radojević Miroslav Čučković Slobodan Šolević |

||

| Area[1] | |||

| - Urban | 359.96 km2 (139 sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 3,222.68 km2 (1,244.3 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation[2] | 117 m (384 ft) | ||

| Population (2007)[3] | |||

| - City | 1,182,000 | ||

| - Density | 506/km2 (1,310.5/sq mi) | ||

| - Urban density | 3,283/km2 (8,502.9/sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 1,630,000 (Table 3.2, p. 64) | ||

| - Demonym | Belgrader | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 11000 | ||

| Area code(s) | (+381) 11 | ||

| Car plates | BG | ||

| Website | www.beograd.rs | ||

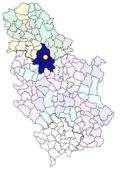

Belgrade (Serbian: Београд, Beograd (listen, pronounced [bɛ'ɔgrad]) is the capital and largest city of Serbia. The city lies at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, where the Pannonian Plain meets the Balkans.[4] With a population of 1,630,000 (official estimate 2007),[3] Belgrade is the fourth largest city in Southeastern Europe, after Istanbul, Athens and Bucharest. Its name in Serbian translates to White city.

Belgrade's wider city area was the birthplace of the largest prehistoric culture of Europe, the Vinča culture, as early as the 6th millennium BC.[5][6] In antiquity, the area of Belgrade was inhabited by the Thraco-Dacian[7] tribe of Singi who would give the name to the city after a fortress was founded in the 3rd century BC by the Celts, who named it Singidun (dun, fortress)[5] It was awarded city rights by the Romans[8] before it was permanently settled by Serbs from the 7th century onwards. As a strategic location, the city was battled over in 115 wars and razed to the ground 44 times[9] since the ancient period by countless armies of the East and West. In medieval times, it was in the possession of Byzantine, Frankish, Bulgarian, Hungarian and Serbian rulers. In 1521 Belgrade was conquered by the Ottomans and became the seat of the Pashaluk of Belgrade, as the principal city of Ottoman Europe[10] and among the largest European cities.[11] Frequently passing from Ottoman to Austrian rule which saw destruction of most of the city, the status of Serbian capital would be regained only in 1841, after the Serbian revolution. Northern Belgrade, though, remained a Habsburg outpost until the breakup of Austria-Hungary in 1918. The united city then became the capital of several incarnations of Yugoslavia, up to 2006, when Serbia became an independent state again.

Belgrade has the status of a separate territorial unit in Serbia, with its own autonomous city government.[12] Its territory is divided into 17 municipalities, each having its own local council.[13] It covers 3.6% of the territory of Serbia, and 24% of the country's population lives in the city.[14] Belgrade is the central economic hub of Serbia, and the capital of Serbian education and science.

Contents |

Geography

Belgrade lies 116.75 metres (383 ft) above sea level and is located at confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers, at coordinates 44°49'14" North, 20°27'44" East. The historical core of Belgrade, today's Kalemegdan, is on the right bank of the rivers. Since the 19th century, the city has been expanding to the south and east, and after World War II, New Belgrade was built on the Sava's left bank, merging Belgrade with Zemun. Smaller, chiefly residential communities across the Danube, like Krnjača and Ovča, also merged with the city. The city has an urban area of 360 square kilometres (139.0 sq mi), while together with its metropolitan area it covers 3,223 km2 (1,244.4 sq mi). Throughout history, Belgrade has been a major crossroads between the West and the Orient.[15]

On the right bank of the Sava, central Belgrade has a hilly terrain, while the highest point of Belgrade proper is Torlak hill at 303 m (994 ft). The mountains of Avala (511 m (1,677 ft)) and Kosmaj (628 m (2,060 ft)) lie south of the city.[16] Across the Sava and Danube, the land is mostly flat, consisting of alluvial plains and loessial plateaus.

Climate

Belgrade has a moderate continental climate, with four seasons and uniformly spread precipitation. The year-round average temperature is 11.7 °C (53.1 °F), while the hottest month is July, with an average temperature of 22.1 °C (71.8 °F). There are, on average, 31 days a year when the temperature is above 30 °C, and 95 days when the temperature is above 25 °C. Belgrade receives about 700 millimeters (27.56 in) of precipitation a year. The average annual number of sunny hours is 2,096. The sunniest months are July and August, with an average of about 10 sunny hours a day, while December and January are the gloomiest, with an average of 2–2.3 sunny hours a day.[17] The highest officially recorded temperature in Belgrade was +43.1 °C,[18] while on the other end, the lowest temperature was −26.2 °C on January 10, 1893.[17]

| Climate data for Belgrade, Serbia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | -2.3 (27.9) |

-0.2 (31.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.8 (46) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.0 (59) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.1 (61) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4 (39) |

-0.2 (31.6) |

7.8 (46) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 47 (1.85) |

44 (1.73) |

46 (1.81) |

56 (2.2) |

71 (2.8) |

91 (3.58) |

67 (2.64) |

53 (2.09) |

51 (2.01) |

46 (1.81) |

57 (2.24) |

59 (2.32) |

688 (27.09) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 145 |

| Sunshine hours | 62 | 85 | 155 | 180 | 210 | 240 | 279 | 279 | 210 | 155 | 90 | 62 | 2,007 |

| Source: [19] | |||||||||||||

History

Ancient city

The Neolithic Starčevo and Vinča cultures existed in Belgrade and dominated the Balkans (as well as parts of Central Europe and Asia Minor) about 7,000 years ago.[20][21] Some scholars believe that the prehistoric Vinča signs represent one of earliest known forms of alphabet.[22] The Paleo-Balkan tribes of Dacians and Thracians dwelled in the area before being settled in the 4th century BC by a Celtic tribe, the Scordisci, the city's recorded name was Singidūn, before becoming the romanized Singidunum in the first century AD. In 34-33BC the Roman army under Silanus reached Belgrade. In the mid 2nd century, the city was proclaimed a municipium by the Roman authorities, evolving into a full fledged colonia (highest class Roman city) by the end of the century.[8] Apart from the first Christian Emperor of Rome who was born on the territory in modern Serbia – Constantine I known as Constantine the Great [23]) – another early Roman Emperor was born in Singidunum: Flavius Iovianus (Jovian), the restorer of Christianity.[24] Jovian reestablished Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, ending the brief revival of traditional Roman religions under his predecessor Julian the Apostate. In 395 AD, the site passed to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire.[21] Across the Sava from Singidunum was the Celtic city of Taurunum (Zemun), that through Roman and Byzantine times shared a common fate with its "twin brother" (the two cities were connected by a bridge).[25]

Middle Ages

Singidunum was occupied and often ravaged by successive invasions of Huns, Sarmatians, Gepids, Ostrogoths and Avars before the arrival of the Slavs around 630 AD. It served as the center of the Gepidean Kingdom in the early 500s, before being taken by the Avars. When the Avars were finally destroyed in the 9th century by the Frankish Kingdom, it fell back to Byzantine rule, whilst Taurunum became part of the Frankish realm (and was renamed to Malevilla).[26] At the same time (around 878), the first record of the Bulgarian name Beligrad has appeared, during the rule of the First Bulgarian Empire. For about four centuries, the city remained a battleground between the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary and the First Bulgarian Empire.[27] The city hosted the armies of the First and the Second Crusade;[28] while passing through during the Third Crusade, Frederick Barbarossa and his 190,000 crusaders saw Belgrade in ruins.[29] Capital of the Kingdom of Syrmia since 1284, the first Serbian king to rule over Belgrade was Dragutin, who received it as a gift from his father-in-law, the Hungarian king Stephen V.[30] Following the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, and the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, the Serbian Empire began to crumble as the Ottoman Empire conquered its southern territory.[31][32] The north, however, resisted through the Serbian Despotate, which had Belgrade as its capital. The city flourished under despot Stefan Lazarević, son of the famous Serbian ruler Lazar Hrebeljanović. Lazarević built a castle with a citadel and towers, of which only the Despot's tower and the west wall remain. He also refortified the city's ancient walls, allowing the Despotate to resist the Ottomans for almost 70 years. During this time, Belgrade was a haven for the many Balkan peoples fleeing from Ottoman rule, and is thought to have had a population of some 40–50,000.[30]

In 1427, Stefan's successor Đurađ Branković had to return Belgrade to the Hungarians, and the capital was moved to Smederevo. During his reign, the Ottomans captured most of the Serbian Despotate, unsuccessfully besieging Belgrade first in 1440[28] and again in 1456.[33] As it presented an obstacle to their further advance into Central Europe, over 100,000 Ottoman soldiers[34] have launched the famous Siege of Belgrade, where the Christian army under John Hunyadi successfully defended the city from the Ottomans, wounding the Sultan Mehmed II[35] This battle "decided the fate of Christendom";[36] the noon bell ordered by Pope Callixtus III commemorates the victory throughout the Christian world to this day.[28][37]

Turkish conquest / Austrian invasions

It was not until August 28, 1521 (7 decades after the last siege), that the fort was finally captured by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent and his 250,000 soldiers; subsequently, most of the city was razed to the ground and its entire Christian population (including Serbs, Hungarians, Greeks, Armenians etc.) was deported to Istanbul,[28] to the area since known as the Belgrade forest.[38] Belgrade was made the seat of the district (Sanjak), attracting new inhabitants—Turks, Armenians, Greeks, Ragusan traders, and others, and there was peace for the next 150 years. The city became the second largest Ottoman town in Europe at over 100,000 people, surpassed only by Constantinople.[34] Turkish rule also introduced Ottoman architecture to Belgrade and many mosques were built, increasing the city's Oriental influences.[39] In 1594, a major Serb rebellion was crushed by the Turks. Further on, Grand vizier Sinan Pasha[40] ordered the relics of Saint Sava to be publicly torched on the Vračar plateau; more recently, the Temple of Saint Sava was built to commemorate this event.[41]

Occupied by Austria three times (1688–1690, 1717–1739, 1789–1791), headed by the Holy Roman Princes Maximilian of Bavaria and Eugene of Savoy,[42] respectively, Belgrade was quickly recaptured and substantially razed each time by the Ottomans.[39] During this period, the city was affected by the two Great Serbian Migrations, in which hundreds of thousands of Serbs, led by their patriarchs, retreated together with the Austrians into the Habsburg Empire, settling in today's Vojvodina and Slavonia.[43]

Serbian capital

During the First Serbian Uprising, the Serbian revolutionaries held the city from January 8, 1807 until 1813, when it was retaken by the Ottomans.[44] After the Second Serbian Uprising in 1815, Serbia reached semi-independence, which was formally recognized by the Porte in 1830.[45] In 1841, Prince Mihailo Obrenović moved the capital from Kragujevac to Belgrade.[46][47]

With the Principality's full independence in 1878, and its transformation into the Kingdom of Serbia in 1882, Belgrade once again became a key city in the Balkans, and developed rapidly.[44][48] Nevertheless, conditions in Serbia as a whole remained those of an overwhelmingly agrarian country, even with the opening of a railway to Niš, Serbia's second city, and in 1900 the capital had only 70,000 inhabitants[49] (at the time Serbia numbered 1,5 million). Yet by 1905 the population had grown to more than 80,000, and by the outbreak of World War I in 1914, it had surpassed the 100,000 citizens, not counting Zemun which then belonged to Austria-Hungary.[50]

The first-ever projection of motion pictures in the Balkans and Central Europe was held in Belgrade in June 1896 by Andre Carr, a representative of the Lumière brothers. He shot the first motion pictures of Belgrade in the next year; however, they have not been preserved.[51]

World War I / Unified city

"Kalemegdan is the prettiest and most courageous piece of optimism I know."

Gavrilo Princip's assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 triggered World War I. Most of the subsequent Balkan offensives occurred near Belgrade. Austro-Hungarian monitors shelled Belgrade on July 29, 1914, and it was taken by the Austro-Hungarian Army under General Oskar Potiorek on November 30. On December 15, it was re-taken by Serbian troops under Marshal Radomir Putnik. After a prolonged battle which destroyed much of the city, between October 6 and October 9, 1915, Belgrade fell to German and Austro-Hungarian troops commanded by Field Marshal August von Mackensen on October 9, 1915. The city was liberated by Serbian and French troops on November 5, 1918, under the command of Marshal Louis Franchet d'Espérey of France and Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia. Decimated as the front-line city, for a while it was Subotica[54] that was the largest city in the Kingdom; still, Belgrade grew rapidly, retrieving its position by the early 1920s.

After the war, Belgrade became the capital of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. The Kingdom was split into banovinas, and Belgrade, together with Zemun and Pančevo, formed a separate administrative unit.[55]

During this period, the city experienced faster growth and significant modernisation. Belgrade's population grew to 239,000 by 1931 (incorporating the town of Zemun, formerly in Austria-Hungary), and 320,000 by 1940. The population growth rate between 1921 and 1948 averaged 4.08% a year.[56] In 1927, Belgrade's first airport opened, and in 1929, its first radio station began broadcasting. The Pančevo Bridge, which crosses the Danube, was opened in 1935.[57]

World War II

On March 25, 1941, the government of regent Crown Prince Paul signed the Tripartite Pact, joining the Axis powers in an effort to stay out of the Second World War. This was immediately followed by mass protests in Belgrade and a military coup d'état led by Air Force commander General Dušan Simović, who proclaimed King Peter II to be of age to rule the realm. Consequently, the city was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe on April 6, 1941, when up to 24,000 people were killed.[58][59] Yugoslavia was then invaded by German, Italian, Hungarian, and Bulgarian forces, and suburbs as far east as Zemun, in the Belgrade metropolitan area, were incorporated into a Nazi state, the Independent State of Croatia. Belgrade became the seat of Nedić's Serbia, headed by General Milan Nedić.

During the summer and fall of 1941, in reprisal for guerrilla attacks, Germans carried out several massacres of Belgrade citizens; in particular, members of the Jewish community were subject to mass shootings at the order of General Franz Böhme, the German Military Governor of Serbia. Böhme rigorously enforced the rule that for every German killed, 100 Serbs or Jews would be shot.[60]

Belgrade had resistance to occupation authorities. Its commander was Major Žarko Todorović Walter. He was arrested in 1943 and taken to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp.

Just like Rotterdam, which was devastated twice, by both German and Allied bombing, Belgrade was bombed once more during World War II, this time by the Allies on April 16, 1944, killing about 1,100 people. This bombing fell on the Orthodox Christian Easter.[61] Most of the city remained under German occupation until October 20, 1944, when it was liberated by Red Army and the Communist Yugoslav Partisans. On November 29, 1945, Marshal Josip Broz Tito proclaimed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia in Belgrade (later to be renamed to Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on April 7, 1963). The communist takeover has resulted in estimated 70,000 deaths across Serbia, up to 10% of which have been carried out in Belgrade. [62] Higher estimates from the former secret police place the victim count of political persecutions in Belgrade at 10,000.[63]

Communist Yugoslavia

During the post-war period, Belgrade grew rapidly as the capital of the renewed Yugoslavia, developing as a major industrial centre.[48] In 1958, Belgrade's first television station began broadcasting. In 1961, the conference of Non-Aligned Countries was held in Belgrade under Tito's chairmanship. In 1968, major student protests against Tito led to several street clashes between students and the police. In March 1972, Belgrade was at the centre of the last major outbreak of smallpox in Europe, which, through enforced quarantine and mass vaccination, was contained by late May.[64]

Post-communist history

On March 9, 1991, massive demonstrations led by Vuk Drašković were held in the city against Slobodan Milošević.[65] According to various media outlets, there were between 100,000 and 150,000 people on the streets.[66] Two people were killed, 203 injured and 108 arrested during the protests, and later that day tanks were deployed onto the streets to restore order.[67] Further protests were held in Belgrade from November 1996 to February 1997 against the same government after alleged electoral fraud at local elections.[68] These protests brought Zoran Đinđić to power, the first mayor of Belgrade since World War II who did not belong to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia or its later offshoot, the Socialist Party of Serbia.[69]

The NATO bombing during the Kosovo War in 1999 caused substantial damage to the city. Among the sites bombed were the buildings of several ministries, the RTS building, which killed 16 technicians, several hospitals, the Jugoslavija Hotel, the Central Committee building, the Avala TV Tower, and the Chinese embassy.[70]

After the elections in 2000, Belgrade was the site of major street protests, with over half a million people on the streets. These demonstrations resulted in the ousting of president Milošević.[71][72]

Names through history

Belgrade has had many different names throughout history, and in nearly all languages the name translates as "the white city". Serbian name Beograd is a compound of beo (“white, light”) and grad (“town, city”), and etymologically corresponds to several other city names spread throughout the Slavdom: Belgorod, Białogard, Biograd etc.

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Singidūn(o)- | Named by the Celtic tribe of the Scordisci; dūn(o)- means 'lodgment, enclosure, fort', and for word 'singi' there are 2 theories—one being that it is a Celtic word for circle, hence "round fort", and the other that the name is Paleo-Balkan and originated from the Singi, a Thracian tribe that occupied the area prior to the arrival of the Scordisci.[73] Another theory suggests that the Celtic name actually bears its modern meaning—the White Fort (town). |

| Singidūnum | Romans conquered the city and Romanized the Celtic name of Singidūn (in turn derived from Paleo-Balkan languages of earlier rulers) |

| Beograd, Београд | Slavic name first recorded in 878 as Beligrad in a letter of Pope John VIII to Boris of Bulgaria which translates to "White city/fortress".[74] |

| Alba Graeca | "Alba" is Latin for "White" and "Graeca" is the possessive "Greek" |

| Alba Bulgarica | Latin name during the period of Bulgarian rule over the city[74] |

| Griechisch-Weißenburg | German translation for "Greek White city". Modern German is Belgrad.[74] |

| Castelbianco | Italian translation for "White castle". Modern Italian is Belgrado.[74] |

| Nandoralba, Nándorfehérvár, Lándorfejérvár | In medieval Hungary. "Fehérvár" means white castle Hungarian - like the Beograd in Serbian. Modern Hungarian is Belgrád.[74] |

| Veligradh(i)on or Velegradha/Βελέγραδα | Byzantine name. Modern Greek is Veligradhi (Βελιγράδι). |

| Dar Al Jihad | Arabic name during Ottoman empire. |

| Prinz-Eugenstadt | Planned German name of the city after the World War II, had it remained a part of the Third Reich. The city was to be named after Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Austrian military commander who conquered the city from the Turks in 1717.[75] |

Government and politics

Belgrade is a separate territorial unit in Serbia, with its own autonomous city government.[12] The current mayor is Dragan Đilas of the Democratic Party. The first mayor to be democratically elected after World War II was Zoran Đinđić, in 1996. Mayors were also elected democratically prior to the war.

The City Assembly of Belgrade has 110 councilors who are elected for four-year terms. The current majority parties are the same as in the Parliament of Serbia (Democratic Party-G17 Plus and Socialist Party of Serbia-Party of United Pensioners of Serbia with the support of Liberal Democratic Party), and in similar proportions, with the Serbian Radical Party and the Democratic Party of Serbia-New Serbia in opposition.[76]

As the capital city Belgrade also seats the National Assembly, Government and its agencies and hosts 64 foreign embassies.

Municipalities

The city is divided into 17 municipalities.[13]

Most of the municipalities are situated on the southern side of the Danube and Sava rivers, in the Šumadija region. Three municipalities (Zemun, Novi Beograd, and Surčin) are on the northern bank of the Sava, in the Syrmia region, and the municipality of Palilula, spanning the Danube, is in both the Šumadija and Banat regions.

| Name | Area (km²) | Population (1991) | Population (2002) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barajevo | 213 | 20,846 | 24,641 | |

| Čukarica | 156 | 150,257 | 168,508 | |

| Grocka | 289 | 65,735 | 75,466 | |

| Lazarevac | 384 | 57,848 | 58,511 | |

| Mladenovac | 339 | 54,517 | 52,490 | |

| Novi Beograd | 41 | 218,633 | 217,773 | |

| Obrenovac | 411 | 67,654 | 70,975 | |

| Palilula | 451 | 150,208 | 155,902 | |

| Rakovica | 31 | 96,300 | 99,000 | |

| Savski Venac | 14 | 45,961 | 42,505 | |

| Sopot | 271 | 19,977 | 20,390 | |

| Stari Grad | 5 | 68,552 | 55,543 | |

| Surčin | 285 | Part of Zemun municipality until 2004. |

55,000 (est.) | |

| Voždovac | 148 | 156,373 | 151,768 | |

| Vračar | 3 | 67,438 | 58,386 | |

| Zemun | 154 | 176,158 | 136,645 | |

| Zvezdara | 32 | 135,694 | 132,621 | |

| TOTAL | 3227 | 1,552,151 | 1,576,124 | |

|

|

||||

Demographics

According to the Census 2002, the main population groups according to nationality in Belgrade are Serbs (1,417,187), Yugoslavs (22,161), Montenegrins (21,190), Roma (19,191), Croats (10,381), Macedonians (8,372), and Muslims by nationality (4,617).[77] Recent polls (2007) show that Belgrade's population has increased by 400,000 in just five years since the last official Census was undertaken.[78]

As of August 2, 2008, the city's Institute for Informatics and Statistics has registered 1,542,773 eligible voters, which confirms that Belgrade's population has risen dramatically since the 2002 Census, as the number of the registered voters has almost surpassed the entire population of the city six years before.[79] The official estimate for the end of 2007 (according to the City's Institute for Informatics and Statistics) was 1,630,000, while the number of registered citizens altogether tops at 1,710,000.[3]

Belgrade is home to many ethnicities from all over the former Yugoslavia. Many people came to the city as economic migrants from smaller towns and the countryside, while thousands arrived as refugees from Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, as a result of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.[80] Between 10,000 and 20,000 [81] Chinese are estimated to live in Belgrade; they began immigrating in the mid-1990s. Blok 70 in New Belgrade is known colloquially as the Chinese quarter.[82][83] Many Middle Easterners, mainly from Syria, Iran, Jordan and Iraq, arrived in order to pursue their studies during the 1970s and 1980s, and have remained and started families in the city.[84][85] Afghani and Iraqi Kurdish refugees are among some of the recent arrivals from the Middle East.[86]

Although there are several historic religious communities in Belgrade, the religious makeup of the city is relatively homogenous. The Serbian Orthodox community is by far the largest, with 1,429,170 adherents. There are also 20,366 Muslims, 16,305 Roman Catholics, and 3,796 Protestants. There used to be a significant Jewish community, but following the Nazi occupation, and many Jews' subsequent emigration to Israel, their numbers have fallen to a mere 415.[3]

Economy

Belgrade is the most economically developed part of Serbia, and is home to the country's National Bank. Many notable companies are based in Belgrade, including Jat Airways, Telekom Srbija, Telenor Serbia, Delta Holding, Elektroprivreda Srbije , Comtrade group, Jat Tehnika, Komercijalna banka, Ikarbus , regional centers for Société Générale, Asus,[87] Intel,[88] Motorola, MTV Adria,[89] Kraft Foods,[90] Carlsberg,[91] Microsoft, OMV, Unilever, Zepter, Japan Tobacco, P&G,[92] and many others.[93][94]

The troubled transition from the former Yugoslavia to the Federal Republic during the early 1990s left Belgrade, like the rest of the country, severely affected by an internationally imposed trade embargo. The hyperinflation of the Yugoslav dinar, the highest inflation ever recorded in the world,[95][96] decimated the city's economy. Yugoslavia overcame the problems of inflation in the mid 1990s, and Belgrade has been growing strongly ever since. Today, over 35% of Serbia's GDP is generated by the city, which also has 31,4% of Serbia's employed population.[97] The average monthly Net pay is 46.500 RSD (€505, $760).[1] According to the Eurostat methodology, and contrasting sharply to the Balkan region, 53% of the city's households own a computer.[98][99] According to the same survey, 39.1% of Belgrade's households have an internet connection; these figures are above those of the regional capitals such as Sofia, Bucharest and Athens.[98]

Culture

Belgrade hosts many annual cultural events, including FEST (Belgrade Film Festival), BITEF (Belgrade Theatre Festival), BELEF (Belgrade Summer Festival), BEMUS (Belgrade Music Festival), Belgrade Book Fair, and the Belgrade Beer Festival.[100] The Nobel prize winning author Ivo Andrić wrote his most famous work, The Bridge on the Drina, in Belgrade.[101] Other prominent Belgrade authors include Branislav Nušić, Miloš Crnjanski, Borislav Pekić, Milorad Pavić and Meša Selimović.[102][103][104] Most of Serbia's film industry is based in Belgrade; the 1995 Palme d'Or winning Underground, directed by Emir Kusturica, was produced in the city.

The city was one of the main centres of the Yugoslav New Wave in the 1980s: VIS Idoli, Ekatarina Velika and Šarlo Akrobata were all from Belgrade. Other notable Belgrade rock acts include Riblja Čorba, Bajaga i Instruktori and others.[105] Today, it is the centre of the Serbian hip hop scene, with acts such as Beogradski Sindikat, Škabo, Marčelo, and most of the Bassivity Music stable hailing from or living in the city.[106][107] There are numerous theatres, the most prominent of which are National Theatre, Theatre on Terazije, Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Zvezdara Theatre, and Atelier 212. The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts is also based in Belgrade, as well as the National Library of Serbia. Other major libraries include the Belgrade City Library and the Belgrade University Library. Belgrade's two opera houses are: National Theatre and Madlenianum Opera House.

There are many foreign cultural institutions in Belgrade including the Spanish Instituto Cervantes, German Goethe-Institut and French Centre Culturel Français which are all located in the central pedestrian Knez Mihailova Street. Other cultural centres in Belgrade are American Corner, Austrian Cultural Forum (Österreichischen Kulturforums), British Council, Chinese Confucius Institute, Canadian Cultural Center, Italian Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Culture Center of Islamic Republic of Iran, Azerbaijani Culture Center and Russian Center for Science and Culture (Российский центр науки и культуры).

Following the victory of Serbia's representative Marija Šerifović at the Eurovision Song Contest 2007, Belgrade hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 2008.[108]

Museums

The most prominent museum in Belgrade is the National Museum, founded in 1844; it houses a collection of more than 400,000 exhibits, (over 5600 paintings and 8400 drawings and prints) including many foreign masterpieces and the famous Miroslavljevo Jevanđelje (Miroslav's Gospel).[109] The Ethnographic Museum, established in 1901, contains more than 150,000 items showcasing the rural and urban culture of the Balkans, particularly the countries of the former Yugoslavia.[110] The Museum of Contemporary Art has a collection of around 35,000 works of art including Andy Warhol, Joan Miró, Ivan Meštrović and others since 1900.[111] The Military Museum houses a wide range of more than 25,000 military exhibits dating as far back as to the Roman period, as well as parts of a F-117 stealth aircraft shot down by Serbian army.[112][113] The Museum of Aviation in Belgrade has more than 200 aircraft, of which about 50 are on display, and a few of which are the only surviving examples of their type, such as the Fiat G.50. This museum also displays parts of shot down US and NATO aircraft, such as the F117 and F16[114] The Nikola Tesla Museum, founded in 1952, preserves the personal items of Nikola Tesla, the inventor after whom the Tesla unit was named. It holds around 160,000 original documents and around 5,700 other items.[115] The last of the major Belgrade museums is the Museum of Vuk and Dositej, which showcases the lives, work and legacy of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and Dositej Obradović, the 19th century reformer of the Serbian literary language and the first Serbian Minister of Education, respectively.[116] Belgrade also houses the Museum of African Art, founded in 1977, which has the large collection of art from West Africa.[117]

With around 95,000 copies of national and international films, the Yugoslav Film Archive is the largest in the region and amongst the 10 largest archives in the world.[118] The institution also operates the Museum of Yugoslav Film Archive, with movie theatre and exhibition hall. The archive's long-standing storage problems were finally solved in 2007, when a new modern depository was opened.[119]

The Belgrade city Museum will move into a new building in Nemanjina Street, downtown. The Museum has interesting exhibits such as the Belgrade Gospel (1503), full plate armour from the Battle of Kosovo, and various paintings and graphics. In 2011 construction will start on a new Museum of Science and Technology.

Architecture

Belgrade has wildly varying architecture, from the centre of Zemun, typical of a Central European town,[120] to the more modern architecture and spacious layout of New Belgrade. The oldest architecture is found in Kalemegdan park. Outside of Kalemegdan, the oldest buildings date only from 18th century, due to its geographic position and frequent wars and destructions.[121] The oldest public structure in Belgrade is a nondescript Turkish turbe, while the oldest house is a modest clay house on Dorćol, from late 18th century.[122] Western influence began in the 19th century, when the city completely transformed from an oriental town to the contemporary architecture of the time, with influences from neoclassicism, romanticism and academic art. Serbian architects took over the development from the foreign builders in the late 19th century, producing the National Theatre, Old Palace, Cathedral Church and later, in the early 20th century, the National Assembly and National Museum, influenced by art nouveau.[121] Elements of Neo-Byzantine architecture are present in buildings such as Vuk's Foundation, old Post Office in Kosovska street, and sacral architecture, such as St. Mark's Church (based on the Gračanica monastery), and the Temple of Saint Sava.[121]

During the period of Communist rule, much housing was built quickly and cheaply to house the huge influx of people from the countryside following World War II, sometimes resulting in the brutalist architecture of the blokovi (blocks) of New Belgrade; a socrealism trend briefly ruled, resulting in buildings like the Trade Union Hall.[121] However, in the mid-1950s, the modernist trends took over, and still dominate the Belgrade architecture.[121]

Tourism

The historic areas and buildings of Belgrade are among the city's premier attractions. They include Skadarlija, the National Museum and adjacent National Theatre, Zemun, Nikola Pašić Square, Terazije, Students' Square, the Kalemegdan Fortress, Knez Mihailova Street, the Parliament, the Temple of Saint Sava, and the Old Palace. On top of this, there are many parks, monuments, museums, cafés, restaurants and shops on both sides of the river. The hilltop Avala Monument offers views over the city. Josip Broz Tito's mausoleum, called Kuća Cveća (The House of Flowers), and the nearby Topčider and Košutnjak parks are also popular, especially among visitors from the former Yugoslavia.

Beli Dvor or 'White Palace', house of royal family Karađorđević, is open for visitors. The palace has many valuable works from Rembrandt, Nicolas Poussin, Sebastien Bourdon, Paolo Veronese, Antonio Canaletto, Biagio d'Antonio, Giuseppe Crespi, Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Ivan Mestrovic, and others.

Ada Ciganlija is a former island on the Sava river, and Belgrade's biggest sports and recreational complex. Today it is connected with the right bank of the Sava via two causeways, creating an artificial lake. It is the most popular destination for Belgraders during the city's hot summers. There are 7 kilometres of long beaches and sports facilities for various sports including golf, football, basketball, volleyball, rugby union, baseball, and tennis.[123] During summer there are between 200,000 and 300,000 bathers daily. Clubs work 24 hours a day, organising live music and overnight beach parties. Extreme sports are available, such as bungee jumping, water skiing and paintballing.[124] There are numerous tracks on the island, where it is possible to ride a bike, go for a walk or go jogging.[125][126] Apart from Ada, Belgrade has total of 16 islands[127] on the rivers, many still unused. Among them, the Great War Island at the confluence of Sava, stands out as an oasis of unshattered wildlife (especially birds).[128] These areas, along with nearby Small War Island, are protected by the city's government as a nature preserve.[129]

Nightlife

Belgrade has a reputation for offering a vibrant nightlife, and many clubs that are open until dawn can be found throughout the city. The most recognizable nightlife features of Belgrade are the barges (сплавови, splavovi) spread along the banks of the Sava and Danube Rivers.[130][131][132]

Many weekend visitors—particularly from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia—prefer Belgrade nightlife to that of their own capitals, due to a perceived friendly atmosphere, great clubs and bars, cheap drinks, the lack of language difficulties, and the lack of restrictive night life regulation.[133][134]

Famous alternative clubs include Akademija and the famed KST (Klub Studenata Tehnike) located in the basement of the University of Belgrade Faculty of Electrical Engineering.[135][136][137] One of the most famous sites for alternative cultural happenings in the city is the SKC (Student Cultural Centre), located right across from Belgrade's highrise landmark, the Beograđanka. Concerts featuring famous local and foreign bands are often held at the centre. SKC is also the site of various art exhibitions, as well as public debates and discussions.[138]

A more traditional Serbian nightlife experience, accompanied by traditional music known as Starogradska (roughly translated as Old Town Music), typical of northern Serbia's urban environments, is most prominent in Skadarlija, the city's old bohemian neighbourhood where the poets and artists of Belgrade gathered in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Skadar Street (the centre of Skadarlija) and the surrounding neighbourhood are lined with some of Belgrade's best and oldest traditional restaurants (called kafanas in Serbian), which date back to that period.[139] At one end of the neighbourhood stands Belgrade's oldest beer brewery, founded in the first half of the nineteenth century.[140] One of the city's oldest kafanas is the Znak pitanja.[141]

The respected Times newspaper in the UK reported that Europe's best nightlife can be found in buzzing Belgrade.[142] In the Lonely Planet "1000 Ultimate Experiences", Belgrade was placed at the 1st spot among the top 10 party cities in the world.[143]

Sport

There are around a thousand sports facilities in Belgrade, many of which are capable of serving all levels of sporting events.[144] Belgrade has hosted several relatively major sporting events recently, including Eurobasket 2005, the 2005 European Volleyball Championship, the 2006 European Water Polo Championship, and the European Youth Olympic Festival 2007. Belgrade was the host city of the 2009 Summer Universiade chosen over the cities of Monterrey and Poznań.[145]

The city launched two unsuccessful candidate bids to organise the Summer Olympic: for the 1992 Summer Olympics Belgrade was eliminated in the third round of International Olympic Committee voting, with the games going to Barcelona. The 1996 Summer Olympics ultimately went to Atlanta.[146][147]

The city is home to Serbia's two biggest and most successful football clubs, Red Star Belgrade and FK Partizan, as well as a few other first league clubs. Red Star are former European Cup winners, in 1991 when they were still representing Yugoslavia. The two major stadiums in Belgrade are the Marakana (Red Star Stadium) and the Partizan Stadium.[148] The rivalry between Red Star and Partizan is one of the most famous capital derbies in Europe and has become known as the Eternal derby. Belgrade Arena is used various sporting events (games of national team in basketball and volleybal as well as Davis Cup matches), and in May 2008 it was the venue of Eurovision Song Contest 2008. Along with Pionir Hall for KK Partizan and KK Crvena zvezda [149][150] while the Tašmajdan Sports Centre is used for swimming competitions and water polo matches.

In recent years, Belgrade has also given rise to several world class tennis players such as Ana Ivanović, Jelena Janković and Novak Đoković. Ivanović and Đoković are the first female and male Serbian players, respectively, to win Grand Slam singles titles.

Media

Belgrade is the most important media hub in Serbia. The city is home to the main headquarters of the national broadcaster Radio Television Serbia - RTS, which is a public service broadcaster.[151] The most popular commercial broadcaster is RTV Pink, a Serbian media multinational, known for its popular entertainment programs. The most popular commercial "alternative" broadcaster is B92, another media company, which has its own TV station, radio station, and music and book publishing arms, as well as the most popular website on the Serbian internet.[152][153] Other TV stations broadcasting from Belgrade include Fox Televizija, Avala, Košava, and others which only cover the greater Belgrade municipal area, such as Studio B. Numerous specialised channels are also available: SOS channel (sport), Metropolis (music), Art TV (art), Cinemania (film), and Happy TV (children's programs).

High-circulation daily newspapers published in Belgrade include Politika, Blic, Večernje novosti, Press, Kurir and Danas. There are 2 sporting dailies, Sportski žurnal and Sport, and one economic daily, Privredni pregled. A new free distribution daily, 24 sata, was founded in the autumn of 2006.

Education

Belgrade has two state universities and several private institutions of higher education. The University of Belgrade, founded in 1808 as the Belgrade Higher School, is the oldest institution of higher learning in Serbia and all of the Balkans.[154] Having developed with the city in the 19th century, quite a few University buildings are a constituent part of Belgrade’s architecture and cultural heritage. The Belgrade University has an enrolment of nearly 90,000 students, placing it under the rubric of Europe's largest universities.[155] The University of Belgrade's Law School is the one of the foremost institutions providing legal education in Central and Eastern Europe.

There are also 195 primary (elementary) schools and 85 secondary schools. Of the primary schools, there are 162 regular, 14 special, 15 art and 4 adult schools. The secondary school system has 51 vocational schools, 21 gymnasiums, 8 art schools and 5 special schools. The 230,000 pupils are managed by 22,000 employees in over 500 buildings, covering around 1,100,000 m².[156]

Transportation

Belgrade has an extensive public transport system based on buses (118 urban lines and more than 300 suburban lines), trams (12 lines), and trolleybuses (8 lines).[157] It is run by GSP Beograd and SP Lasta, in cooperation with private companies on various bus routes. Belgrade also has a commuter rail network, Beovoz, now run by city government. The main railway station connects Belgrade with other European capitals and many towns in Serbia. Travel by coach is also popular, and the capital is well-served with daily connections to every town in the country.

The city is placed along the pan-European corridors X and VII.[4] The motorway system provides for easy access to Novi Sad and Budapest, the capital of Hungary, in the north; Niš to the south; and Zagreb, to the west. Situated at the confluence of two major rivers, the Danube and the Sava, Belgrade has 7 bridges—the two main ones are Branko's bridge and Gazela, both of which connect the core of the city to New Belgrade. With the city's expansion and a substantial increase in the number of vehicles, congestion has become a major problem; this is expected to be alleviated by the construction of a bypass connecting the E70 and E75 highways.[158] Further, an "inner magistral semi-ring" is planned, including a new Ada Bridge across the Sava river, which is expected to ease commuting within the city and unload the Gazela and Branko's bridge.[159] Two additional bridges are planned, both over the Danube.

The Port of Belgrade is on the Danube, and allows the city to receive goods by river.[160] The city is also served by Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport (IATA: BEG), 12 kilometres west of the city centre, near Surčin. At its peak in 1986, almost 3 million passengers travelled through the airport, though that number dwindled to a trickle in the 1990s.[161] Following renewed growth in 2000, the number of passengers reached approximately 2 million in 2004 and 2005.[162] In 2006, 2 million passengers passed through the airport by mid-November,[163] while during the 2007 the figure peaked at 2,5 million customers.[164]

Beovoz is the suburban/commuter railway network that provides mass-transit services in the city, similar to Paris's RER and Toronto's GO Transit. The main usage of today's system is to connect the suburbs with the city centre. Beovoz is operated by Serbian Railways.[165] Belgrade suburban railway system connects suburbs and nearby cities to the west, north and south of the city. It began operation in 1992 and currently has 5 lines with 41 stations divided in two zones.[166] Stations in the city centre are built underground, out of which station Vukov spomenik is the deepest at 40 meters.[167]

While Belgrade does not have a metro/subway, it has been planned. The Belgrade Metro is considered to be the third most important project in the country, after work on roads and railways. The two projects of highest priority are the Belgrade bypass and Pan-European corridor X.

International cooperation and honours

These are the official sister cities of Belgrade:[168][169][170][171]

| Country | City | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Corfu | 2010 | |

| Coventry | 1957 | |

| Chicago | 2005 | |

| Lahore | 2007 | |

| Tel Aviv | 1990 | |

| Vienna | 2003 |

Some of the city's municipalities are also twinned to small cities or districts of other big cities, for details see their respective articles.

Other similar forms of cooperation and city friendship:

| Country | City | Date | Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athens | 1966 | Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation | |

| Banja Luka | 2005 | Agreement on Cooperation | |

| Beijing | 1980 | Agreement on Cooperation[172] | |

| Berlin | 1978 | Agreement on Cooperation and Friendship | |

| Düsseldorf | 2004 | Agreement on Cooperation | |

| Kiev | 2002 | Agreement on Cooperation | |

| Madrid | 2001 | Agreement on Cooperation | |

| Milan | 2000 | Memorandum of Agreement, City to City Programme | |

| Moscow | 2002 | Programme of Cooperation | |

| Rome | 1971 | Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation | |

| Shenzhen | 2009 | Agreement on Cooperation[173] | |

| Skopje | June, 2006 | Agreement on Cooperation[174] |

The City of Belgrade has received various domestic and international honours, including the French Légion d'honneur (proclaimed December 21, 1920; Belgrade is one of four cities outside France, alongside Liège, Luxembourg and Volgograd, to receive this honour), the Czechoslovak War Cross (awarded October 8, 1925), the Yugoslavian Karađorđe's Star with Swords (awarded May 18, 1939) and the SFR Yugoslavian Order of the National Hero (proclaimed on October 20, 1974, the 30th anniversary of the overthrow of Nazi German occupation during World War II).[175] All of these decorations were received for the war efforts during the World War I and World War II.[176] In 2006, Financial Times' magazine Foreign Direct Investment awarded Belgrade the title of City of the Future of Southern Europe.[177][178] In 2008, the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network (GaWC), based at the geography department of Loughborough University, published their roster of leading world cities. Belgrade is in the fourth category out of five on this list, being listed in the group of the cities with a "high sufficiency" world presence.[179]

See also

- List of notable Belgraders

- Singidunum

- Kalemegdan

References

Bibliography

- Pavić, Milorad (2000). A Short History of Belgrade. Belgrade: Dereta. ISBN 86-7346-117-0.

- Tešanović, Jasmina (2000). The Diary of a Political Idiot: Normal Life in Belgrade. Cleis Press. ISBN 1-57344-114-7.

- Levinsohn, Florence Hamlish (1995). Belgrade : among the Serbs. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-061-4.

- Paton, Andrew Archibald (2005-11-04) [1845] (Reprint by Project Gutenberg/Project Rastko). Servia, Youngest Member of the European Family: or, A Residence in Belgrade, and Travels in the Highlands and Woodlands of the Interior, during the years 1843 and 1844.. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. http://pge.rastko.net/dirs/1/6/9/9/16999/16999-h/16999-h.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

Notes

- ↑ "Territory". Official website of City of Belgrade. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201197. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Geographical Position". Official website of City of Belgrade. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201029. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Statistical yearbook of Belgrade" (pdf, link IE only). Zavod za informatiku i statistiku Grada Beograda. 2007. p. 64. https://zis.beograd.gov.rs/upload/G_2007E.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "City of Belgrade - Why invest in Belgrade?". Beograd.org.yu. http://www.beograd.org.yu/cms/view.php?id=1299561. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Discover Belgrade". Official Website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=320. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Tasic N, Srejovic D, Stojanovic B (1990). Vinca, Centre of the Neolithic culture of the Danubian region. Project Rastko - E-library of Serb Culture. http://www.rastko.rs/arheologija/vinca/vinca_eng.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ http://www.beogradskatvrdjava.co.rs/start/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=17&Itemid=378

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rich, John (1992). The City in Late Antiquity. CRC Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780203130162. http://books.google.com/?id=_uMP91pRf0UC&pg=PA113&lpg=PA113. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Robert Nurden (2009-03-22). "Belgrade has risen from the ashes to become the Balkans' party city". London: Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/belgrade-has-risen-from-the-ashes-to-become-the-balkans-party-city-1651037.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "The History of Belgrade". BelgradeNet Travel Guide. http://www.belgradenet.com/belgrade_history_middle_ages.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Turkish and Austrian Rule". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201251. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Assembly of the City of Belgrade". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201014. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Urban Municipalities". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201906. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "2005 Municipal indicators of Republic of Serbia". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/axd/en/pok.php?god=2005. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ "Geographical Position". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201029. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Natural Features". Official site. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201033. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Climate". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201193. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ m&c News (2007-07-24). "Record-breaking heat measured in Belgrade". http://news.monstersandcritics.com/europe/news/article_1334095.php/Record-breaking_heat_measured_in_Belgrade. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ↑ "Average Weather for Belgrade, Serbia - Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. http://www.climate-charts.com/Locations/y/YG13274.php#data. Retrieved December, 2009.

- ↑ Nikola Tasić; Dragoslav Srejović, Bratislav Stojanović (1990). "Vinča and its Culture". In Vladislav Popović. Vinča: Centre of the Neolithic culture of the Danubian region. Smiljka Kjurin (translator). Belgrade. http://www.rastko.org.rs/arheologija/vinca/vinca_eng.html#_Toc504111710. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "History (Ancient Period)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201172. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Kitson, Peter (1999). Year's Work in English Studies Volume 77. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 9780631212935. http://books.google.com/?id=iWlpqkVMX2YC&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Constantine I - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9109633/Constantine-I. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "Philologic Results-Bot-generated title->". Artfl.uchicago.edu. http://artfl.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.25:1:283.harpers. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "City of Belgrade - Ancient Period". Beograd.rs. 2000-10-05. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201172. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "History of Zemun". Geocities.com. 1914-07-28. http://www.geocities.com/kadezi/zemunhistory.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ The History of Belgrade

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 "How to Conquer Belgrade - History". Beligrad.com. 1934-12-16. http://www.beligrad.com/history.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "The History of Belgrade". Belgradenet.com. http://www.belgradenet.com/belgrade_history.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "History (Medieval Serbian Belgrade)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201247. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Battle of Maritsa". Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9050991/Battle-of-the-Maritsa-River. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Battle of Kosovo". Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9046112/Battle-of-Kosovo. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Ćorović, Vladimir (1997). "V. Despot Đurađ Branković" (in Serbian). Istorija srpskog naroda. Banja Luka / Belgrade: Project Rastko. ISBN 86-7119-101-X. http://www.rastko.org.rs/rastko-bl/istorija/corovic/istorija/4_5_l.html. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "The History of Belgrade". Belgradenet.com. http://www.belgradenet.com/belgrade_history_middle_ages.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Tom R. Kovach. "Ottoman-Hungarian Wars: Siege of Belgrade in 1456". Military History magazine. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history/3030796.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Romanian Heritage | Heritage / JohnHunyadi". Wiki.viitorulroman.com. 2006-10-15. http://wiki.viitorulroman.com/pmwiki.php/Heritage/JohnHunyadi. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Hungary: A Brief History

- ↑ "The Rough Guide to Turkey: Belgrade Forest". Rough Guides. http://www.roughguides.co.uk/website/travel/Destination/content/default.aspx?titleid=104&xid=idh573385336_0211. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "History (Turkish and Austrian Rule)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201251. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Welcome to Frosina.org :: An Albanian Immigrant and Cultural Resource". Frosina.org. http://www.frosina.org/culturehistory/reviews.asp?id=121. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Amfilohije Radović (1989). "Duhovni smisao hrama Svetog Save na Vračaru (Online book reprint)" (in Serbian). Janus, Belgrade. http://www.mitropolija.me/dvavoda/knjige/aradovic-hram_l.html. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ "Belgrade Fortress: History". Razgledanje.tripod.com. 2004-08-23. http://razgledanje.tripod.com/tvrdjava/english.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Medaković, Dejan (1990). "Tajne poruke svetog Save" Svetosavska crkva i velika seoba Srba 1690. godine". Oči u oči. Belgrade: BIGZ (online reprint by Serbian Unity Congress library). ISBN 978-8613009030. http://www.suc.org/culture/library/Oci/tajne-poruke-svetoga-save-16-03-03.html. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "History (Liberation of Belgrade)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201255. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Pavkovic, Aleksandar (2001-10-19). Nations into States: National Liberations in Former Yugoslavia. The Australian National University.

- ↑ "History of Kragujevac". Official website of Kragujevac. http://www.kragujevac.rs/en/history.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ "History (Important Years Through City History)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201239. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "History (The Capital of Serbia and Yugoslavia)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201259. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Jan Lahmeyer (2003-02-03). "The Yugoslav Federation: Historical demographical data of the urban centers". www.populstat.info. http://www.populstat.info/Europe/yugoslft.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑

"Belgrade and Smederevo" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia - Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

"Belgrade and Smederevo" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia - Retrieved on 2007-10-16. - ↑ Kosanovic, Dejan (1995). "Serbian Film and Cinematography (1896-1993)". The history of Serbian Culture. Porthill Publishers. ISBN 1-870732-31-6. http://www.rastko.org.rs/isk/dkosanovic-cinematography.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Serbia :: Belgrade". Balkanology. http://www.balkanology.com/serbia/article_belgrade.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ http://www.serbworldusa.com/REBECCA%20WEST.html

- ↑ "Serbia :: Vojvodina". Balkanology. http://www.balkanology.com/serbia/article_vojvodina.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ ISBN 86-17-09287-4: Kosta Nikolić, Nikola Žutić, Momčilo Pavlović, Zorica Špadijer: Историја за трећи разред гимназије, Belgrade, 2002, pg. 144

- ↑ Petrović, Dragan (2001). "Industrija i urbani razvoj Beograda" (PDF). Industrija 21 (1–4): 87–94. ISSN 0350-0373. http://scindeks.nb.rs/article.aspx?artid=0350-03730101087P&redirect=ft. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Twentieth Century - Innovations in Belgrade". Serbia-info.com (Government of Serbia website). Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. http://web.archive.org/web/20080118092237/http://www.serbia-info.com/g3/images/1930-50-e.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Stevenson, William (1976). A Man Called Intrepid, The Secret War. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 230. ISBN 345-27254-4-250.

- ↑ "Part Two the Yugoslav Campaign". THE GERMAN CAMPAIGN IN THE BALKANS (SPRING 1941). United States Army Center of Military History. 1986 [1953]. CMH Pub 104-4. http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/balkan/20_260_2.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Rubenstein, Richard L; Roth, John king (2003). Approaches to Auschwitz: The Holocaust and Its Legacy. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 170. ISBN 0664223532. http://www.questia.com/library/book/approaches-to-auschwitz-the-holocaust-and-its-legacy-by-john-k-roth-richard-l-rubenstein.jsp.

- ↑ "Anniversary of the Allied Bomb Attacks Against Belgrade". Radio-Television of Serbia. 2008-04-17. http://www.spc.rs/eng/anniversary_allied_bomb_attacks_against_belgrade. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ http://www.napredniklub.org/tekstovi.php?subaction=showfull&id=1255532834&archive=&start_from=&ucat=1&

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/14429469/Izmedju-Srpa-i-Cekica

- ↑ "Bioterrorism: Civil Liberties Under Quarantine". NPR. 2001-10-23. http://www.npr.org/news/specials/response/anthrax/features/2001/oct/011023.quarantine.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Prvi udarac Miloševićevom režimu" (in Serbian). Danas. 2006-03-09. http://www.danas.rs/20060309/hronika1.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ James L. Graff (1991-03-25). "Yugoslavia: Mass bedlam in Belgrade". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,972607-1,00.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Srbija na mitinzima (1990–1999)" (in Serbian). Vreme. 1999-08-21. http://www.vreme.com/arhiva_html/450/2.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "History (Disintegration Years 1988–2000)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201267. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Jane Perlez (1997-02-23). "New Mayor of Belgrade: A Serbian Chameleon". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40616F83B5A0C708EDDAB0894DF494D81&n=Top%2fReference%2fTimes%20Topics%2fPeople%2fD%2fDjindjic%2c%20Zoran. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ "NATO bombing". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201271. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ "Parties, citizens mark October 5". B92. 2007-10-05. http://www.b92.net//eng/news/politics-article.php?yyyy=2007&mm=10&dd=05&nav_category=90&nav_id=44315. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "October 5, 2000". Official website. http://www.beograd.org.yu/cms/view.php?id=201275. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Ancient Period". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201172. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 "History (Byzantine Empire)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201243. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ "Opasno neznanje ili nešto više". Danas. http://www.danas.rs/vesti/dijalog/opasno_neznanje_ili_nesto_vise.46.html?news_id=145464. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ "Councilors of the Assembly of the City of Belgrade". Official site. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201942. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ "Facts (Population)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201201. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Blic Online | Tema dana | Svi putevi vode u Beograd". Blic.rs. 2007-10-29. http://www.blic.rs/temadana.php?id=17781. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "Birački spisak" (in Serbian). Zavod za informatiku i statistiku Grada Beograda. 2007. https://zis.beograd.gov.rs/spisak.php.

- ↑ Refugee Serbs Assail Belgrade Government: The Washington Post, Tuesday, June 22, 1999.

- ↑ Stranci tanje budžet Novosti - Vecernje novosti - Beograd

- ↑ "Kinezi Marko, Miloš i Ana" (in Serbian). Kurir. 2005-02-20. http://arhiva.kurir-info.rs/Arhiva/2005/februar/19-20/B-01-19022005.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Biljana Vasić (2001-01-15). "Kineska četvrt u bloku 70" (in Serbian). Vreme. http://www.vreme.com/arhiva_html/471/10.html. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Vesna Peric Zimonjic (2005-12-07). "A unique friendship club in Belgrade". Dawn - International. http://www.dawn.com/2005/12/07/int17.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ Francesca Ciriaci (1999-04-11). "Government, public diverge in assessment of Kosovo crisis". Jordan Times. http://www.jordanembassyus.org/041199003.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ "CHINESE AND IRAQI IMMIGRANTS RECEIVE QUIET WELCOME". international. 2007-05-31. http://ins.onlinedemocracy.ca/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=9214. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ↑ Asus otvorio regionalni centar u Beogradu :: emportal :: Ekonomske vesti iz Srbije

- ↑ "Centar kompanije `Intel` za Balkan u Beogradu - Srbija deo `Intel World Ahead Program`". E kapija. http://www.ekapija.com/website/sr/page/140159. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "Vesti dana : MTV se preselio u Beograd : POLITIKA". Politika.rs. http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/vesti-dana/MTV-se-preselio-u-Beograd.lt.html. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ↑ Beograd će biti regionalni centar :: emportal :: Ekonomske vesti iz Srbije

- ↑ "Beograd konkuriše Beču". Politika. 2008-02-21. http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/Ekonomija/Beograd-konkurishe-Bechu.lt.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Procter&Gamble Belgrade

- ↑ "JTI u Srbiju ulaže oko $100 mil." (in Serbian). B92 Biz. 2007-04-24. http://www.b92.net/biz/vesti/srbija.php?yyyy=2007&mm=04&dd=24&nav_id=243493&fs=1. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Beograd - Bankarski razvojni centar" (in Serbian). 24x7 business news. 2006-03-29. http://www.24x7.co.yu/default.aspx?cid=400&fid=300&pid=izbor_societe_generale_group. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Watkins, Thayer. "The Worst Episode of Hyperinflation in History: Yugoslavia 1993-94". Episodes of Hyperinflation. San José State University Department of Economics. http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/hyper.htm#YUGO. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ↑ Taylor, Bryan. "Countries that Suffered the Greatest Inflation in the Twentieth century" (Word document). The Century of Inflation. Global Financial Data. pp. 8, 10. http://www.globalfindata.com/articles/Century_of_Inflation.doc. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ↑ "Privreda Beograda" (in Serbian). Economic Chamber of Belgrade. http://www.kombeg.org.rs/privredabg/privreda.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 "U Srbiji sve više računara". Politika.rs. http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/Drustvo/U-Srbiji-sve-vishe-rachunara.lt.html. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Almost 98% of companies in Serbia are computerised - Economy.rs

- ↑ "Culture and Art (Cultural Events)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201299. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "The biography of Ivo Andrić". The Ivo Andrić Foundation. http://www.ivoandric.org.rs/html/biography.html. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ "Borislav Pekić - Biografija" (in Serbian). Project Rastko. http://www.rastko.org.rs/knjizevnost/nauka_knjiz/pekic-biograf.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Joseph Tabbi (2005-07-26). "Miloš Crnjanski and his descendents". Electronic Book Review. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/internetnation/sumatrism. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Meša Selimović - Biografija" (in Bosnian). Kitabhana.net. http://www.xs4all.nl/~eteia/kitabhana/Selimovic_Mehmed_Mesa/Biografija.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Riblja Čorba" (in Serbian). Balkan Media.com. http://www.balkanmedia.com/magazin/hall/corba/biografija2.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Aleksandar Pavlić (2005-02-09). "Beogradski Sindikat: Svi Zajedno" (in Serbian). Popboks magazine. http://www.popboks.com/albumi/beogradskisindikat.shtml. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ S. S. Todorović (2004-01-30). "Liričar među reperima" (in Serbian). Balkanmedia. http://www.balkanmedia.com/m2/doc/3184-1.shtml. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ "Serbian ballad wins Eurovision Song Contest - Belgrade hosts in 2008". Helsingin Sanomat. 2007-05-14. http://www.hs.fi/english/article/Serbian+ballad+wins+Eurovision+Song+Contest+-+Belgrade+hosts+in+2008+/1135227223254. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Tatjana Cvjetićanin. "From the history of the National Museum in Belgrade". National Museum of Serbia. http://www.narodnimuzej.rs/code/navigate.php?Id=75. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ↑ "Museums 3". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201167. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Museums 2". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201055. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Museums". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201283. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "World Guide:Belgrade". Lonely Planet. http://www.lonelyplanet.com/worldguide/destinations/europe/serbia/belgrade?v=print. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ↑ "Lična karta Muzeja ratnog vazduhoplovstva" (in Serbian). Museum of Air force Belgrade. http://www.muzejrv.org/istorija/istorija.html. Retrieved 1007-05-19.

- ↑ "About the museum". Nikola Tesla Museum. http://www.tesla-museum.org/meni_en/nt.php?link=muzej/m&opc=sub2. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "City of Belgrade - Museums 1". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201051. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Cultural institutions:Museum of African Art". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=202308. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Action programme 2006 for Serbia: Support to the Yugoslav Film Archive" (PDF). European Agency for Reconstruction. 2006-01-01. http://www.ear.europa.eu/serbia/main/documents/2006Media.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "New Depository for the Yugoslav Film Archive’s treasure". SEECult.org, Culture Portal of Southeastern Europe. 2007-06-07. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20071011202918/http://seecult.org/english/module-News-display-sid-211.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Nicholas Comrie, Lucy Moore (2007-10-01). "Zemun: The Town Within the City". B92 Travel. http://www.b92.net/eng/travel/index.php?nav_id=38986. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 121.2 121.3 121.4 Zoran Manević. "Architecture and Building". MIT website. http://web.mit.edu/most/www/ser/Belgrade/zoran_manevic.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Mihajlo Mitrović (2003-06-27). "Seventh Belgrade triennial of world architecture". ULUS. http://www.ulus.org.rs/ENGLISH/Exhibitions/TriennialA/TriennialA.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Sportski tereni" (in Serbian). Public utility "Ada Ciganlija". http://www.adaciganlija.rs/sport_tereni.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Ada Ciganlija". Tourism Organisation of Belgrade. http://www.tob.rs/english/zasto_bg/zeleni_bg/ada/index.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "O Adi" (in Serbian). Public utility "Ada Ciganlija". http://www.adaciganlija.rs/o_adi.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Kupalište" (in Serbian). Public utility "Ada Ciganlija". http://www.adaciganlija.rs/s_tereni/kupaliste.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Ana Nikolov (2005-07-29). Beograd – grad na rekama. Institut za Arhitekturu i Urbanizam Srbije. http://www.ekapija.com/website/sr/page/17516. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ↑ "Zbogom, oazo!" (in Serbian). Kurir. 2006-05-23. http://arhiva.kurir-info.rs/Arhiva/2006/maj/23/B-01-23052006.shtml. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ↑ Beoinfo (2005-08-04). "Prirodno dobro "Veliko ratno ostrvo” stavljeno pod zaštitu Skupštine grada" (in Serbian). Ekoforum. http://www.ekoforum.org/index/vest.asp?vID=181. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ↑ Eve-Ann Prentice (2003-08-10). "Why I love battereBelgrade". London: The Guardian Travel. http://travel.guardian.co.uk/article/2003/aug/10/observerescapesection1. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Seth Sherwood (2005-10-16). "Belgrade Rocks". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/16/travel/16belgrade.html?ex=1287115200&en=4cd8ccf41a41542c&ei=5088. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Barbara Gruber (2006-08-22). "Belgrade's Nightlife Floats on the Danube". Deutsche Welle. http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2129528,00.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Slovenci dolaze u jeftin provod" (in Serbian). Glas Javnosti. 2004-12-21. http://www.b92.net/info/vesti/pregled_stampe.php?yyyy=2004&mm=12&dd=21&nav_id=158386. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "U Beograd na vikend-zabavu" (in Croatian). Večernji list. 2006-01-06. Archived from the original on 2006-01-06. http://www.b92.net/info/vesti/pregled_stampe.php?yyyy=2006&mm=01&dd=08&nav_id=184523. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Gordy, Eric D. (1999). "The Destruction of Musical Alternatives". The Culture of Power in Serbia: Nationalism and the Destruction of Alternatives. Penn State Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 0271019581. http://books.google.com/?id=WqoZsrmYZQIC&dq=Belgrade+KST. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Intro". Club "Akademija". http://www.akademija.net/remote/?call=2&lg=2. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Klub Studenata Tehnike - O nama" (in Serbian). http://www.kst.org.rs/.

- ↑ "Student cultural center". SKC. http://www.skc.rs/info.php?lang=2. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Skadarlija". Tourist Organisation of Belgrade. http://www.tob.rs/english/zasto_bg/bg_amb/skadarlija/index.html. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Beogradska Industrija Piva AD". SEE News. http://www.seenews.com/profiles/companies/cs_bip_beogradska_industrija_piva/. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Znamenite građevine 3" (in Serbian). Official site. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=1319. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Scurlock, Gareth (2008-11-04). "Europe's best nightlife". London: Official site. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/travel/holiday_type/music_and_travel/article5082856.ece. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ "The world's top 10 party towns". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2009-11-09. http://www.smh.com.au/travel/the-worlds-top-10-party-towns-20091118-im4q.html. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ "Sport and Recreation". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201508. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Universiade 2009 (Belgrade)". FISU. Archived from the original on 2008-02-09. http://web.archive.org/web/20080209234741/http://www.fisu.net/site/page_1068.php. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "History of the Olympic Committee of Serbia". Olympic Committee of Serbia. http://www.oks.org.rs/s101e.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Atlanta 1996". Official Website of the Olympic Movement. http://www.olympic.org/uk/past/index_uk.asp?OLGT=1&OLGY=1996. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Sport and Recreation (Stadiums)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201754. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Sport and Recreation (Sport Centers and Halls)". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201758. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Venues". EYOF Belgrade 2007. http://www.beograd2007.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=20&Itemid=131&limit=1&limitstart=3&lang=en. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ↑ "Samo RTS može da bude javni servis". Radio Television of Serbia. 2005-08-23. http://www.rts.rs/jedna_vest.asp?belong=&IDNews=125391.

- ↑ Jared Manasek (2005-01). "The Paradox of Pink". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. http://web.archive.org/web/20070930033327/http://www.cjr.org/issues/2005/1/manasek-paradox.asp. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "B92 na 8.598. mestu na svetu" (in Serbian). B92. 2006-09-01. http://www.b92.net/info/vesti/index.php?yyyy=2006&mm=09&dd=01&nav_category=15&nav_id=210237&fs=1. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "The University of Belgrade – The Seedbed of University Education". Faculty of Law of University of Belgrade. http://www.ius.bg.ac.rs/eng/university_of_belgrade.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ "Универзитет у Београду - Број Студената" (in Serbian). University of Belgrade. http://www.bg.ac.rs/csrp/univerzitet/br_studenata.php. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ↑ "Education and Science". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201008. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Statistics". Public Transport Company "Belgrade". http://www.gsp.rs/english/statistic.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Belgrade Bypass, Serbia". CEE Bankwatch network. http://www.bankwatch.org/project.shtml?w=147584&s=1961998. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "1. faza prve deonice Unutrašnjeg magistralnog poluprstena" (in Serbian) (PDF). Belgrade Direction for Building and Real Estate Land/EBRD. 2005-07-01. http://www.ebrd.com/projects/eias/34913s.pdf. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- ↑ "History of the Port of Belgrade". Port of Belgrade. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927092246/http://www.port-bgd.co.yu/en/history.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ "Airports and Flying fields". Aviation guide through Belgrade. http://www.vazduhoplovnivodic.rs/eng/eng_letelista.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Regionalni centar putničkog i kargo saobraćaja" (in Serbian). Danas. 2005-05-20. http://www.danas.rs/20050520/ekonomija1.html. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ ""Nikola Tesla" Airport received its two millionth passenger". Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport. 2006-11-14. http://www.beg.aero/code/navigate.php?Id=130#775. Retrieved 2006-05-18.

- ↑ "www.beg.aero | Nikola Tesla Belgrade Airport | News". Airport-belgrade.rs. http://www.airport-belgrade.rs/code/navigate.php?Id=63. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Železnice Srbije - Red voznje Beovoz-a

- ↑ Grad Beograd - Beovoz

- ↑ “Vukov Spomenik” Beograd, Srbija

- ↑ "International Cooperation". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=1225698. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Beograd: Međunarodni odnosi". Stalna konferencija gradova i opština Srbije. http://www.skgo.org/php/opstine/detalji.php?Id=12&IdSvojstva=MO. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ↑ "Council okays peace committees: Lahore and Chicago to be declared twin cities.". The Post. 2007-01-28. http://thepost.com.pk/Arc_CityNews.aspx?dtlid=79932&catid=3&date=01/28/2007&fcatid=14. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ↑ "Bratimljenje Beograda i Krfa". B92. http://www.b92.net/info/vesti/index.php?yyyy=2010&mm=02&dd=25&nav_category=12&nav_id=414000. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. http://www.ebeijing.gov.cn/Sister_Cities/Sister_City/. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ "Saradnja Beograda i Šendžena". B92. http://www.b92.net/info/vesti/index.php?yyyy=2009&mm=07&dd=11&nav_category=12&nav_id=370774. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ "City of Belgrade - International Cooperation". Beograd.rs. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=1225698. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ↑ "Received Decorations". Official website. http://www.beograd.rs/cms/view.php?id=201227. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ↑ "Beograd - grad heroj". RTV Pink. 2009-11-06. http://www.rtvpink.com/vesti/vest.php?id=26907. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ↑ "European Cities of the Future 2006/07". fDi magazine. 2006-02-06. http://www.fdimagazine.com/news/fullstory.php/aid/1543. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Aleksandar Miloradović (2006-09-01). "Belgrade - City of the Future in Southern Europe" (PDF). TheRegion, magazine of SEE Europe. http://www.seeurope.net/files2/pdf/rgn0906/13_Belgrade_CityOfTheFutureInSEE.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "The World According to GaWC 2008". Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network (GaWC). Loughborough University. http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2008t.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

External links

- City of Belgrade Official Website

- Tourist Organization of Belgrade

- Belgrade Chamber of Commerce

- Standing Conference of Towns and Municipalities

- Environmental Atlas of Belgrade, Institute of Public Health of Belgrade

- Belgrade travel guide from Wikitravel

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||